Acing the Diplomatic Mission

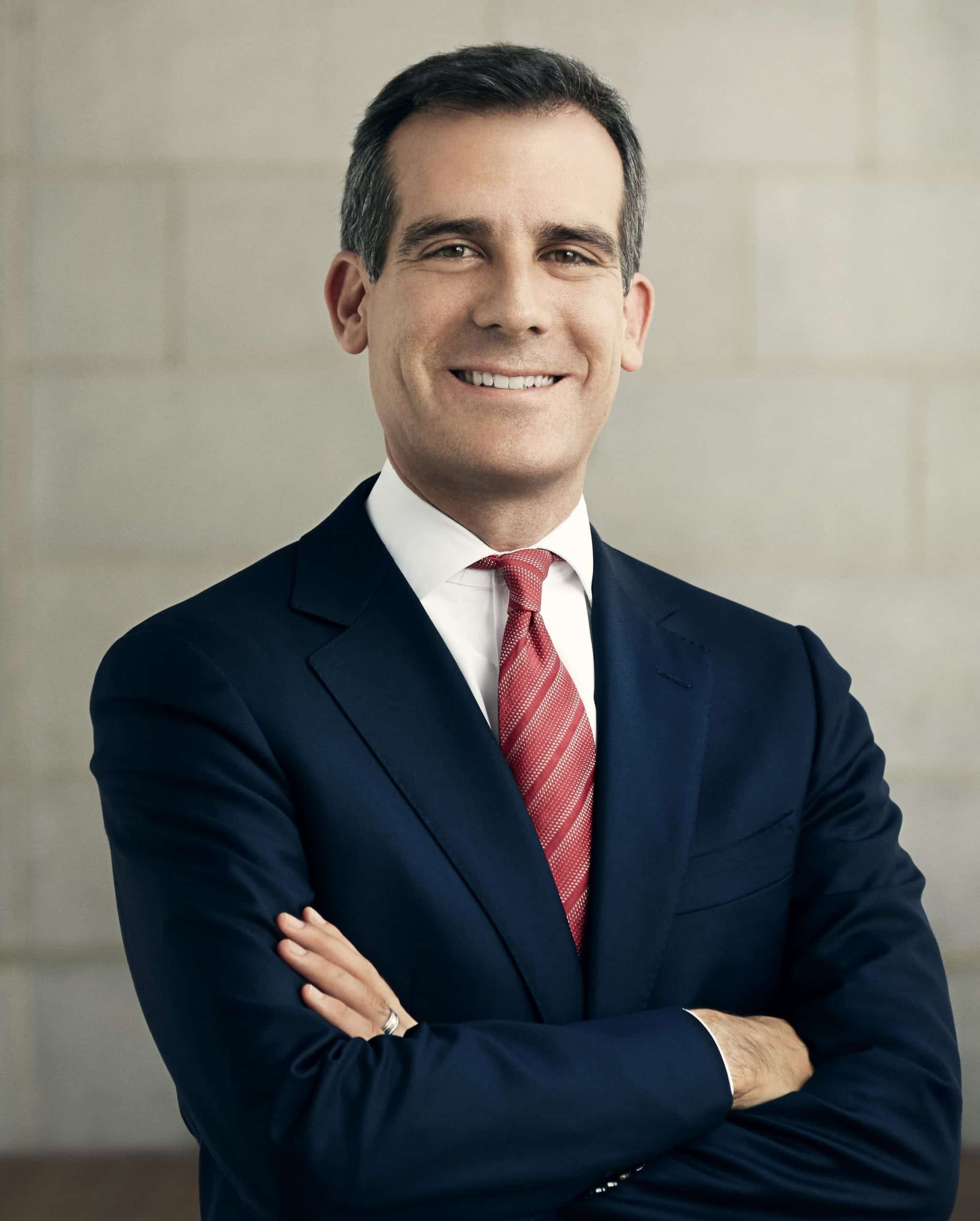

The United States has not had an ambassador in New Delhi for a little over two years now, from the time Kenneth Juster packed up from Roosevelt House on January 20, 2021, when there was a change of guard at the White House. It is the longest stretch New Delhi has been without a US ambassador. When Thomas Pickering was moved to Moscow in March 1993 after serving as US ambassador in New Delhi for just under a year, it took the Clinton White House 14 months to nominate the next envoy, Frank Wisner. The delay was seen in some quarters as a slight -- to a country which at that time was a relative lightweight and distant partner to the US in a unipolar world. Kenneth Brill, a distinguished US Foreign Service official, served as chargé d'affaires between March 1993 – August 1994. Still, it was seen as a snub for a coveted station that has seen some of America's greatest diplomats. In July 1963, two of America's finest literally crossed each other at the threshold -- Chester Bowles going to New Delhi even as John Kenneth Galbraith was exiting. So what explains this two year hiatus in New Delhi that has been filled by five charge d'affaires while an ambassadorial nominee waits in the wings for confirmation in Washington? Well, the one obvious answer is the famed Washington gridlock arising from deeply partisan politics.  Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti was originally nominated by President Biden to be the U.S. ambassador to India on July 9, 2021. Eighteen months later, he is yet to wing his way to New Delhi. His confirmation was stalled in the previous Senate over accusations that he ignored sexual assault and harassment allegations against a former top aide. The President has re-nominated him earlier this month, saying he has "confidence in Mayor Garcetti and believes he will be an excellent representative in India at a critical moment and calls for the Senate to swiftly confirm him." Even if he leaves for New Delhi next month, he will likely hold the record as the longest ambassador-in-waiting. Typically, large and important countries get as ambassadors political appointees who have the ear and often a direct line to the President. JK Galbraith was a Kennedy confidante, and the story goes that he frequently bypassed his notional boss, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, to go directly to the President, once writing to him that trying to communicate via Rusk was "like trying to fornicate through a mattress." Chester Bowles, Kenneth Keating and Daniel Moynihan, all political appointees who went to New Delhi after Galbraith, were heavyweights in their own right, having served in the House and Senate. Starting in 1980 though, Washington sent a series of career foreign service officials (fso) to serve as ambassadors in New Delhi. Although some of them were distinguished careerists -- Pickering and Wisner among them -- it wasn't until Bill Clinton, preparatory to his visit to India in 2000, sent Richard Celeste, a former Governor of Ohio, that political appointees became the norm again. Since then, with the exception of Nancy Powell in 2012-2014, all US ambassadors to New Delhi have been political appointees: Robert Blackwill, David Mulford, Timothy Roemer, Richard Verma, and Kenneth Juster. Most of them have sailed through the confirmation process in politically propitious times, when India’s growing heft begged for a quick shoo-in. But such is the prevalent pathology in Washington that all bets are off when it comes to a political appointee even when global strategic developments cry out for a quick replacement. India is not alone in this regard. Saudi Arabia has not had a US ambassador for almost as long. Two years into its terms, the Biden White House still hasn’t managed to get ambassadors in 40 world capitals. Would a career foreign service officer, especially one of Indian-origin, have gone through faster for New Delhi? Probably, but he or she would have lacked the clout and access that a political appointee carries. The good news in the long run is more Indians in America are entering the world of diplomacy, both through the career foreign service track and the political path. In 2011, when then President Obama, named career fso Geeta Pasi as ambassador to Djibouti, and later to Chad, it was a breakthrough moment. In 2017, President Trump nominated another career fso, Krishna Urs, as ambassador to Peru. In between, there have been political nominees too: In 2014, President Obama nominated Richard Verma, a former congressional staffer and military vet, to serve as the US ambassador in New Delhi; almost concurrently, Nisha Desai Biswal, also a former Hill staffer, was the US Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia – a unique double for the Indian diaspora. Soon after, Taranjit Sandhu, India’s current ambassador to Washington, and Atul Keshap, a career fso, served as Indian and American ambassadors to Sri Lanka. And most recently, while Ambassador Sandhu’s wife Reenat Sandhu is India’s ambassador to the Netherlands, President Biden has sent to The Hague as ambassador Democratic Party operative Shefali Razdan Duggal.

Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti was originally nominated by President Biden to be the U.S. ambassador to India on July 9, 2021. Eighteen months later, he is yet to wing his way to New Delhi. His confirmation was stalled in the previous Senate over accusations that he ignored sexual assault and harassment allegations against a former top aide. The President has re-nominated him earlier this month, saying he has "confidence in Mayor Garcetti and believes he will be an excellent representative in India at a critical moment and calls for the Senate to swiftly confirm him." Even if he leaves for New Delhi next month, he will likely hold the record as the longest ambassador-in-waiting. Typically, large and important countries get as ambassadors political appointees who have the ear and often a direct line to the President. JK Galbraith was a Kennedy confidante, and the story goes that he frequently bypassed his notional boss, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, to go directly to the President, once writing to him that trying to communicate via Rusk was "like trying to fornicate through a mattress." Chester Bowles, Kenneth Keating and Daniel Moynihan, all political appointees who went to New Delhi after Galbraith, were heavyweights in their own right, having served in the House and Senate. Starting in 1980 though, Washington sent a series of career foreign service officials (fso) to serve as ambassadors in New Delhi. Although some of them were distinguished careerists -- Pickering and Wisner among them -- it wasn't until Bill Clinton, preparatory to his visit to India in 2000, sent Richard Celeste, a former Governor of Ohio, that political appointees became the norm again. Since then, with the exception of Nancy Powell in 2012-2014, all US ambassadors to New Delhi have been political appointees: Robert Blackwill, David Mulford, Timothy Roemer, Richard Verma, and Kenneth Juster. Most of them have sailed through the confirmation process in politically propitious times, when India’s growing heft begged for a quick shoo-in. But such is the prevalent pathology in Washington that all bets are off when it comes to a political appointee even when global strategic developments cry out for a quick replacement. India is not alone in this regard. Saudi Arabia has not had a US ambassador for almost as long. Two years into its terms, the Biden White House still hasn’t managed to get ambassadors in 40 world capitals. Would a career foreign service officer, especially one of Indian-origin, have gone through faster for New Delhi? Probably, but he or she would have lacked the clout and access that a political appointee carries. The good news in the long run is more Indians in America are entering the world of diplomacy, both through the career foreign service track and the political path. In 2011, when then President Obama, named career fso Geeta Pasi as ambassador to Djibouti, and later to Chad, it was a breakthrough moment. In 2017, President Trump nominated another career fso, Krishna Urs, as ambassador to Peru. In between, there have been political nominees too: In 2014, President Obama nominated Richard Verma, a former congressional staffer and military vet, to serve as the US ambassador in New Delhi; almost concurrently, Nisha Desai Biswal, also a former Hill staffer, was the US Assistant Secretary of State for South Asia – a unique double for the Indian diaspora. Soon after, Taranjit Sandhu, India’s current ambassador to Washington, and Atul Keshap, a career fso, served as Indian and American ambassadors to Sri Lanka. And most recently, while Ambassador Sandhu’s wife Reenat Sandhu is India’s ambassador to the Netherlands, President Biden has sent to The Hague as ambassador Democratic Party operative Shefali Razdan Duggal.

Chidanand Rajghatta is the Times of India’s US-based Foreign Editor, long-time Washington D.C. scribe and sutradhar. In earlier roles, Rajghatta has worked with India’s leading news brands, including The Indian Express, The Telegraph of Kolkata, India Today, and The Sunday Times of India. He received his Master's Degree in mass communication from Bangalore University, Bangalore. He is the author of The Horse That Flew: How India's Silicon Gurus Spread Their Wings, Illiberal India: Gauri Lankesh and the Age of Unreason and Kamala Harris: Phenomenal Woman.

Chidanand Rajghatta is the Times of India’s US-based Foreign Editor, long-time Washington D.C. scribe and sutradhar. In earlier roles, Rajghatta has worked with India’s leading news brands, including The Indian Express, The Telegraph of Kolkata, India Today, and The Sunday Times of India. He received his Master's Degree in mass communication from Bangalore University, Bangalore. He is the author of The Horse That Flew: How India's Silicon Gurus Spread Their Wings, Illiberal India: Gauri Lankesh and the Age of Unreason and Kamala Harris: Phenomenal Woman.